Date: May 21, 2014

Time: 2:00 - 6:00 PM MDT

Place: Denver, Byers, Colorado

Distance: 1012 mi (424 positioning, 87 chasing, 501 to home)

Camera: T3i, GoPro3 Silver & Black, Lumix

Warnings: SVR, TOR

Rating: S5

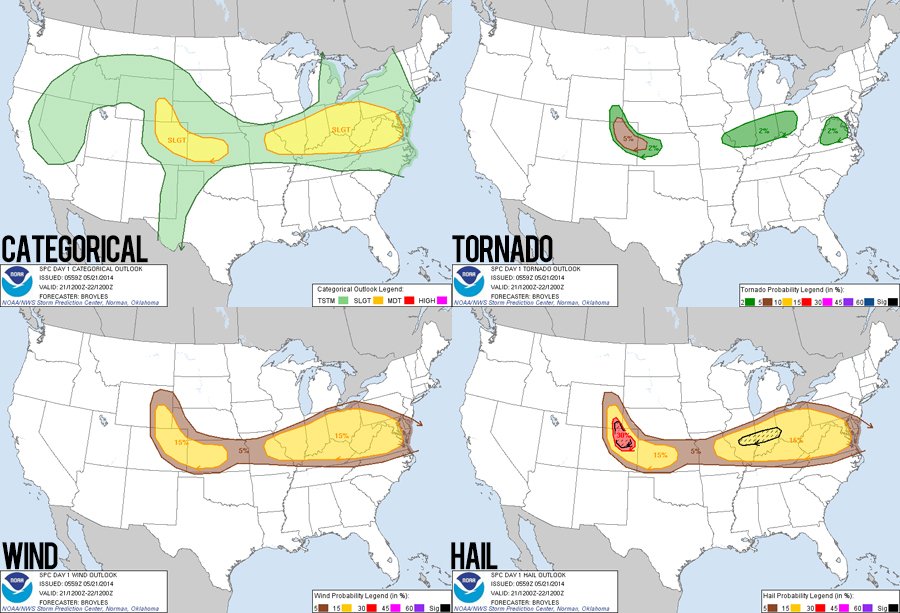

Forecast and Set Up

A Colorado upslope play in May?? Usually this is the type of setup that you chase at the tail end of a season as the jet stream migrates north into Canada. Added to the rather unusual setup (for the time of year), today was also a difficult mid-week chase bookended by workdays. Basically, this was a microcosm of the slow and often frustrating 2014 storm season. That said, a chase in the beautiful Colorado high plains is never a bad thing.

The previous evening, we made the eleventh-hour decision to chase this setup and drove 3 hours north to Trinidad, CO - lessening the miles we'd have to travel today. Examining morning models, I was reminded how unskilled I still am at parsing the subtleties of these upslope storm days (dryline days in central Kansas are a piece of cake in comparison). These setups are rather unusual because they occur after a backdoor cold front has passed through, which pulls modest 50 degree dewpoints west towards the Rockies, as was the case today. At the same time, a decent upper level flow was moving nearly 180 degrees in the opposite direction, causing a sharp turning of winds with height. But thermodynamics seemed rather weak with forecast 1000 J/Kg CAPE values. Nevertheless, my confidence was bolstered by the HRRR which consistently showed a supercell tracking over the Denver metro by mid-afternoon. And I'm not one to doubt the Palmer Divide and Denver Convergence Vorticity Zone magic.

We left Trinidad late morning and headed north on I-25 – stopping to get some copter shots of the striking Huerfano Butte as we drove north. We were just passing Monument, CO at 1 PM when the first SVR warning was issued for a cell still over the Front Range southwest of Denver. We could also see towers building north of us over Denver itself. By 1:30, we had arrived in Lone Tree (the southernmost Denver suburb) as storms were exploding just to our north over the city center. Toni needed a quick coffee pit stop, and then the chase began!

The Chase

We never chase in big cities, but I initially thought we could safely go north on I-25, cut across on I-225, and then race east on I-70 to put a little distance between us and the storm. Unfortunately, Toni’s coffee stop (or, you could argue, any of our other brief stops earlier in the day) proved fateful and we were about 5 minutes late – blocked by the now beautifully-structured and tornado-warned cell crossing 225. So one exit south of 225, we bailed onto surface streets to find a new path. Being stuck in stop-and-go traffic is just about the worst feeling when reports of a tornado are already beginning to trickle in.

At the Cherry Creek Reservoir, we got our first clear view of the southern side of the storm. During this brief stop, I never saw any clear areas of organized rotation, but upon looking at footage later I may have captured a little nub funnel. This occurred about 5 minutes after a reported tornado on the ground in the same area.

The next 45 minutes were pretty frustrating as we fought our way out of the eastern Denver suburbs – catching glimpses of the storm between houses and trees. During this time, the supercell consolidated and began moving straight east down I-70 – taking on an absolutely massive hook, one of the more impressive reflectivity signatures I’ve seen. The storm was headed directly towards the Denver airport and the KFTG radar, and I was a little worried we might lose our radar coverage if the doppler dome was damaged.

After eventually breaking free of Denver traffic, we intercepted the storm just south of Bennett and got our first somewhat clear view of the mesocyclone. I say “somewhat clear” because of the unexpectedly HP nature of the storm - surprising given the relatively modest moisture. Nevertheless, we could still see rapid motion in the rain bands and very intimidating upward motion. To enable some timelapse opportunities, we dashed about 15 miles east on I-70 and pulled off at Byers. After an hour, we were finally out in front of the storm with some breathing room. My favorite part of the chase could commence!

Unfortunately, the supercell wasn’t looking nearly as impressive as it had 15 minutes earlier. The massive hook was gone and we could see outflow racing south out of the storm. It was either dying or recycling. Trying to get a little better look at a possible new mesocyclone, we drifted a few miles north onto a dirt road. Here, we had an awesome view of the interface between the storm’s RFD trying to surge from the west and the inflow coming from the southeast. Lots of interesting non-tornadic swirls – both clockwise and counterclockwise – developed at this interface and it was absolutely fascinating to watch. Adding to the spectacle, we had amazing lighting conditions with deep blues of the storm contrasted with the bright greens of the fields. Some of my favorite timelapse sequences were capture at this point. As a final bonus, the RFD/inflow interface provided some relatively calm air so that we could deploy the quadcopter for a few minutes!

We lingered at this location for nearly 20 minutes, and more storm chasers joined us as time went on. David Hoadley (the first known storm chaser) even pulled up right beside us, but I was too shy to introduce myself. Eventually, we needed to reposition as it appeared that large scale rotation was ramping up again. Dropping back to Hwy 36, the only scare of the day occurred as we were met with an enormous train of chasers streaming east – rendering a left turn nearly impossible and trapping us right in the path of the surging RFD and reforming hook. Just as the RFD began to overtake us, the traffic thinned and we escaped east. Though traffic was orderly, I was still a little nervous as this was by far the largest chaser convergence I’d ever seen, and I tallied 109 vehicles as we made our way further east hoping to get ahead of the hoard.

Several miles down the road, we pulled off on a dirt road topping a big rolling hill. From this great vantage, we could safely watch the storm wrapping up behind us (plus we were far enough ahead of the chaser crowd that we didn’t need to hunt for a parking spot). Almost immediately, a new wallcloud developed directly in front of us with decent rotation. This feature appeared to be a cross between a classic wallcoud and RFD outflow arc and it took on several beautiful shapes – at one point exhibiting pleasing flanges at its base. Once again, I was thrilled by the amazing structure, colors, and lighting for timelapse shots. The wallcloud wrapped up north into the core of the precipitation and fell apart. We hadn’t realized it yet, but this was the last hurrah for our storm. To the southwest, new storms were firing in the trailing cold pool and interfering with the primary supercell. Over the next 15 minutes, our storm fell apart rapidly as a bulge of new convection developed directly on top of us (precisely as the HRRR had predicted) and dropped some small hail.

We opted to let these new storms move on to the northeast, as none looked particularly strong or organized. In the calm air behind the departing storms, I was able to fly the quadcopter one last time, filming the last dying columns of cumulus that had once been our impressive supercell. On the way back home to Albuquerque, we stopped in Denver and tried Hawaiian BBQ for the first time (apparently their version of BBQ sauce is brown gravy). Then we listen to the 3rd book in the Hitchhiker's Guide series on the long drive back home.

Recap, Filmmaking Notes, and Lessons Learned

- The High Resolution Rapid Refresh (HRRR) model has absolutely been on fire lately. It nailed every aspect of today's setup: initiation, timing, location, and storm death. This is like living in the future; I've never seen storm-scale models perform this well.

- Little delays can have major consequences on storm positioning.

- As impressive as our supercell appeared, it only produced very weak and brief tornadoes (still haven't seen any definitive photos).

- Like the Konova slider, the aerial shots from my quadcopter have a visual languange that I am just beginning to appreciate. A forward-dip-then-rise has a great introductory feel, while a backward-rising shot gives a distinct feeling of finality.

- After the chase, I drove till 2AM to make it all the way home. While I remained mostly alert, I did have a rather strange experience. I can remember the drive itself, but the last two hours of Hitchhiker's Guide were completely dumped from my memory. Listening to it again later, I had zero recollection of the book's ending.